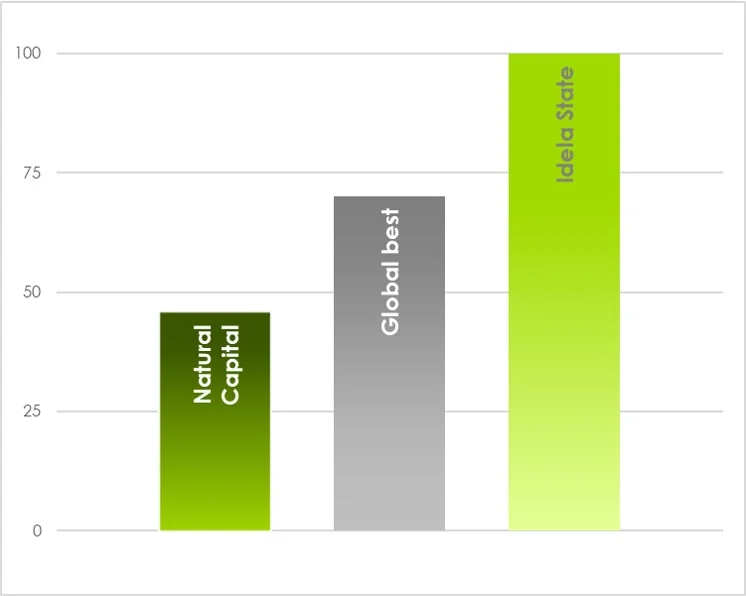

Natural Capital defines a country's ability to support and sustain its population and economy. It encompasses the stock of renewable and non-renewable natural resources—including forests, water, fertile soil, minerals, and biodiversity—that provide the foundation for all economic activity and human well-being. The Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index measures how effectively countries manage and preserve their natural capital for current and future generations.

State of Natural Capital 2024

Key Insights from the Natural Capital Index 2024

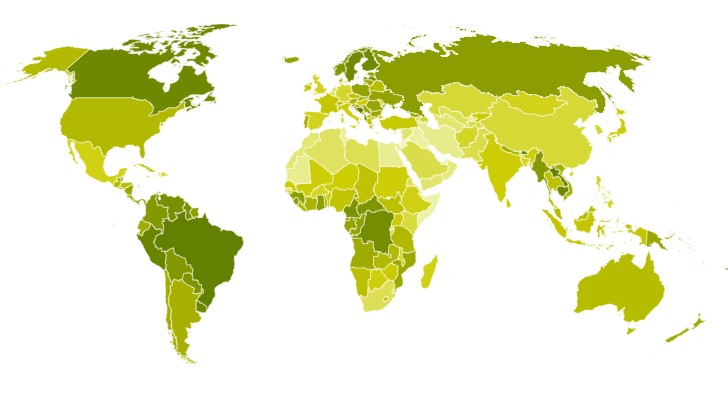

- Resource-rich nations with low population density dominate the top rankings, including Canada, Russia, Australia, and Brazil

- Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden, Norway) rank highly due to extensive forests, clean water, and responsible resource management

- Small island nations face natural capital constraints due to limited land area and vulnerability to climate change

- Densely populated countries with limited natural resources (Japan, Netherlands, Singapore) rank lower but compensate through innovation and resource efficiency

- Many African countries possess significant natural capital but face challenges with governance and sustainable management

- Climate change is accelerating natural capital degradation globally, particularly affecting water resources and agricultural land

- Deforestation, soil degradation, and biodiversity loss continue at alarming rates despite international commitments

Understanding Natural Capital

Natural Capital represents the world's stocks of natural assets. Unlike human-made capital that can be manufactured, natural capital develops over geological timescales or through complex ecological processes. Once degraded or destroyed, many forms of natural capital cannot be restored within human timeframes. This makes preservation and sustainable management essential for long-term prosperity.

Key Components of Natural Capital:

- Forests and Vegetation: Timber resources, carbon sequestration, biodiversity habitat, and watershed protection

- Water Resources: Freshwater availability, quality, and distribution for agriculture, industry, and human consumption

- Agricultural Land: Soil quality, arable land availability, and productive capacity for food production

- Mineral Resources: Non-renewable resources including metals, fossil fuels, and industrial minerals

- Biodiversity: Species diversity and ecosystem health that support ecological resilience and services

- Climate Stability: Atmospheric composition and climate systems that enable agriculture and habitation

Regional Analysis: Natural Endowments and Challenges

Resource-Rich Nations: Abundance and Responsibility

Canada, Russia, Brazil, and Australia possess exceptional natural capital relative to their populations. Vast forests, abundant freshwater, extensive agricultural land, and significant mineral deposits create enormous economic potential. However, with this abundance comes responsibility. These nations face pressure to exploit resources for economic gain while preserving ecosystems for future generations and global climate stability.

Canada and the Nordic countries demonstrate that natural wealth can be managed sustainably through strong governance frameworks and environmental regulations. Russia and Brazil face greater challenges—Russia from inadequate environmental enforcement, Brazil from deforestation pressure in the Amazon. The Amazon rainforest alone contains 10% of global biodiversity and plays a critical role in global climate regulation, making Brazil's stewardship decisions globally significant.

Densely Populated Developed Nations: Innovation Through Scarcity

Japan, the Netherlands, and Singapore rank lower in natural capital due to limited land area, dense populations, and minimal natural resources. However, these constraints have driven exceptional innovation in resource efficiency. The Netherlands pioneered advanced agricultural techniques that produce high yields from limited land. Japan leads in materials science and recycling technologies. Singapore achieves water self-sufficiency through desalination and water recycling despite having no natural freshwater sources.

These examples demonstrate that natural capital scarcity can be partially compensated through technological innovation and efficient resource management. However, this compensation has limits—these nations remain vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and depend on natural capital from other countries through trade.

Africa: Endowment Without Returns

Many African nations possess significant natural capital—the Democratic Republic of Congo holds vast mineral wealth and rainforests, Angola and Nigeria have extensive oil reserves, and the continent overall contains abundant agricultural potential. Yet these endowments often fail to translate into prosperity due to governance challenges, conflict, and exploitation.

The "resource curse" affects many African nations: abundant natural resources can undermine democratic development, fuel corruption, and create economic dependencies on commodity exports. Without strong institutions and governance capacity, natural wealth becomes a source of conflict rather than prosperity. Climate change compounds these challenges through desertification, water scarcity, and agricultural disruption.

Small Island Developing States: Vulnerability and Resilience

Small island nations face unique natural capital challenges. Limited land area restricts agricultural potential and biodiversity. Rising sea levels and increasing storm intensity from climate change threaten their very existence. Coral reef degradation—occurring globally but particularly critical for island nations—eliminates natural storm barriers and fishery resources.

Despite these constraints, some island nations demonstrate remarkable resilience through marine resource management, ecotourism, and climate adaptation strategies. However, their vulnerability to global climate change—largely caused by larger nations—creates a profound injustice that international governance mechanisms have yet to adequately address.

The Natural Capital World Map 2024

Why Natural Capital Matters for Sustainability

Natural Capital is the foundation upon which all economic activity and human well-being depend. Without clean air, water, fertile soil, and stable climate systems, no amount of financial or human capital can sustain prosperity. The Natural Capital Index reveals critical insights:

- Economic Foundation: Agriculture, forestry, fisheries, mining, and tourism directly depend on natural resources. Many industries that seem divorced from nature rely on natural capital inputs

- Ecosystem Services: Natural systems provide services—pollination, water purification, climate regulation, flood control—that would be prohibitively expensive to replace with technology

- Resource Security: Nations with diverse, well-managed natural capital are more resilient to supply chain disruptions and less vulnerable to resource price volatility

- Climate Stability: Forests and oceans absorb carbon dioxide, moderate temperatures, and regulate rainfall patterns essential for agriculture and habitation

- Social Stability: Resource scarcity and environmental degradation drive migration, conflict, and social tensions. Access to clean water and productive land affects billions of lives

- Intergenerational Equity: Natural capital degradation creates liabilities for future generations who inherit depleted resources and damaged ecosystems

Natural capital is not optional—it is the foundation of all prosperity

Countries that preserve and sustainably manage their natural capital create the conditions for long-term economic prosperity, social stability, and resilience to global challenges including climate change and resource scarcity.

Protecting Natural Capital: Policy Pathways

Countries looking to preserve and enhance their Natural Capital should prioritize:

- Protected Areas: Establishing and effectively managing protected areas that preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functions

- Sustainable Forestry: Preventing deforestation while enabling sustainable timber harvesting and forest product industries

- Water Management: Ensuring sustainable freshwater use through efficient irrigation, watershed protection, and pollution control

- Soil Conservation: Preventing erosion and degradation through sustainable agricultural practices and land use planning

- Biodiversity Protection: Preserving species diversity through habitat conservation and combating wildlife trafficking

- Climate Mitigation: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions to prevent further climate-driven natural capital degradation

- Circular Economy: Transitioning from linear "take-make-dispose" models to circular systems that minimize resource extraction and waste

- Natural Capital Accounting: Incorporating environmental costs and benefits into economic decision-making and national accounts

- Environmental Enforcement: Strengthening regulations and enforcement against pollution, illegal resource extraction, and ecosystem destruction

The Economic Case for Natural Capital Protection

Protecting natural capital is not just environmentally responsible—it is economically rational:

- Ecosystem services provide an estimated $125-$140 trillion in annual economic value globally—roughly 1.5 times global GDP

- Deforestation costs the global economy $2-$5 trillion annually through lost ecosystem services

- Water scarcity already affects 2 billion people and constrains economic activity in many regions

- Pollinator decline threatens $235-$577 billion in annual crop production globally

- Climate change driven by natural capital degradation creates trillions in economic damages through extreme weather, agricultural losses, and displacement

- Countries with well-managed natural resources attract sustainable tourism, foreign investment, and premium prices for certified sustainable products

The Natural Capital Crisis

Current trends in natural capital are deeply concerning. Despite decades of environmental awareness and international agreements:

- Global biodiversity continues declining, with species extinction rates 100-1000 times higher than natural background rates

- Deforestation proceeds at approximately 10 million hectares per year, releasing stored carbon and eliminating ecosystem services

- Soil degradation affects 33% of global land area, threatening food security for billions

- Ocean acidification from CO₂ absorption threatens marine ecosystems and fisheries

- Freshwater scarcity intensifies due to overextraction, pollution, and climate change

- Climate feedback loops accelerate as melting permafrost releases methane and reduced ice coverage decreases planetary reflectivity

These trends demonstrate that current approaches to natural capital management are inadequate. The gap between international commitments and actual environmental outcomes reveals the need for transformative change in how societies value and manage natural resources.

Addressing the natural capital crisis requires integrating environmental considerations into all economic and political decisions. This means pricing environmental costs into goods and services, redirecting subsidies from environmentally harmful activities to sustainable alternatives, and strengthening international cooperation on transboundary environmental challenges. Countries that lead in natural capital protection will gain competitive advantages as resource scarcity intensifies and environmental regulations strengthen globally.

Explore Further

For more detailed analysis and country-specific Natural Capital data, visit the interactive Global Sustainable Competitiveness Index or download the full GSCI 2024 Report.